Miracle on 35th Street

(December 3, 1956)

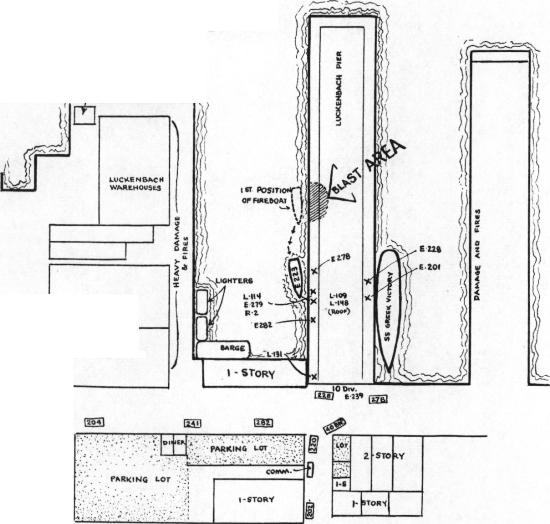

At 3:16 P.M. on December 3, 1956, the Brooklyn Central Office received a telephone alarm for a fire on the pier at the foot of 35th Street, Brooklyn and transmitted Box 1499. The pier is 175' x 1740' with a concrete deck and a one-story steel shed. The fire started in foam rubber on the north side of the pier about 750 feet from the land end and spread to nearby inflammable cargo before the arrival of Department units. To the present writing, the cause of the fire has not been definitely determined. Four minutes after the original alarm was transmitted, Act. Lieut. Al Kraemer, Eng. Co. 228, sent in the second. The third, fourth and fifth alarms were sent in at intervals of approximately seven minutes. Shortly after the fifth alarm was transmitted but before the fourth and fifth alarm assignments were in position — heavy traffic in the area slowed down their response — the blast occurred. Two Borough Calls were subsequently sent out. This article is confined to the reactions of the members on the scene to the awe-inspiring blast. It is hoped that an article in a future issue will cover the technical aspects of the fire and the methods by which it was fought.

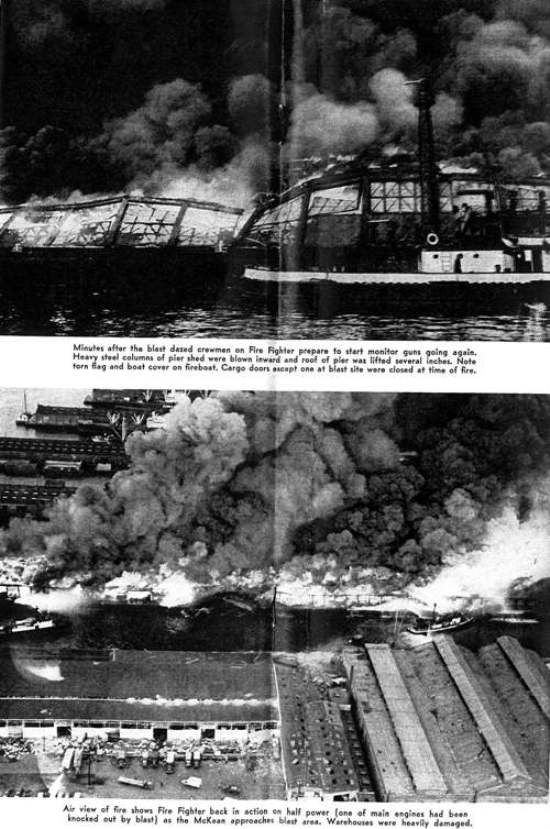

When the Firefighter (E. 223) responded on the box from its pier to the south, it headed for the fire showing out the only open cargo door on the pier. They tied up in front of the door and started all deck guns on the blaze. Minutes later, as 3rd alarm units were coming into position, Chief Fred Bahr (25th Bn.) ran down the pier from the land end and observed that, despite the heavy streams, the fire was making headway toward theland end. He called to the Firefighter to shut down and move shoreward about 200 feet.

Fireman John Gallagher had just secured the bow line in the new position when the explosion flattened him on deck. The explosion occurred at the very spot where the boat had been minutes before. John Lorenz, above the pilot house, was adjusting the monitors to the new position. He was blown along the deck on his stomach. His arm caught in the chain rail as he went over, dangling him neatly in front of the pilot house windows where Capt. John Loehr and Pilot Joe Clinton retrieved him. They too, had been flattened by the concussion and sprayed with flying glass as every window in the pilot house (save 3 which were down) was blown to smithereens. John Kelly was on the monitor deck too — he found himself going down the stairway on all fours. Joe Carriello was operating the controls at the base of the tower which helped to protect him. He remembers only a "whooshing" sound whereas all the others heard the tremendous noise of the blast. The engineers below (Lou DeMars, Charles Nekiunas and Roy Nicholson) wereblown about like peas in a bottle. The port engine went dead.

Back on the pier, abreast the Firefighter, Eng. 278 was about to take a line from the boat when the blast knocked Lt. Tom Coughlin into the water. He tried to climb onto the pilings but found that his shoulder was injured. He was rescued by the combined efforts of members of the Firefighter and those on the pier. He and Sal Di Salvio were carried off the pier in severe shock.

Just shoreward of Eng. 278, Lt. Albert Chall and men of Eng. 282 were operating their line in a cargo door. The Lieutenant was blown overboard by the blast. Pat Sessa was thinking what a seat those spectators on the south pier had of the fire. When he looked up an instant after the explosion the pier was bare. Joe Szal stood rooted to the spot, then threw himself face down on the dock. Bill O'Donnell had never heard anything like it. He dove to the side of the pier shed for protection. Out in the street a little north of the pier MPO Jim Hanley heard the blast. High piles of cargo on the water side helped shield him but as debris rained down he dove for a warehouse door which disintegrated in front of him. A live wire made him jig until he cleared it.

Ladders 148 and 109 were operating on the roof of the pier when the blast came. Ed Grandin thought he could feel the roof move and then land in place again. He held flat to the roof, hoping nothing heavy would fall on him. Harry Ware thought he was walking on air. John LoPrest felt the same sensation. He wondered why he had ever left the Police Dept. Dick Sachinis thought his eyes were playing tricks on him as the building bucked like a storm-tossed ship. Lieut. Robert Fox, a 40-year veteran of the Department, thought: "This is far and away the biggest thing I've ever run into." A lower Manhattan Office worker said he saw the A-bomb effect lift the roof and settle it down again.

Ray Hellriegel and Jim Heffernan, Department Photographers, were responding to the fire and were about to stop their car at the crest of the high bridge over Gowanus Canal to take a "long shot" of the blaze. As they slowed down, the blast occurred and the car rocked from the concussion. Ray pulled up on the emergency brake and both jumped from the car, cameras in hand. They saw the flames shooting hundreds of feet into the air — like the "mushroom" of an atomic bomb — but before they could get a picture it dissipated. They made up for this bad luck a few minutes later, getting 1,800 feet of color movies and many of the photos shown here.

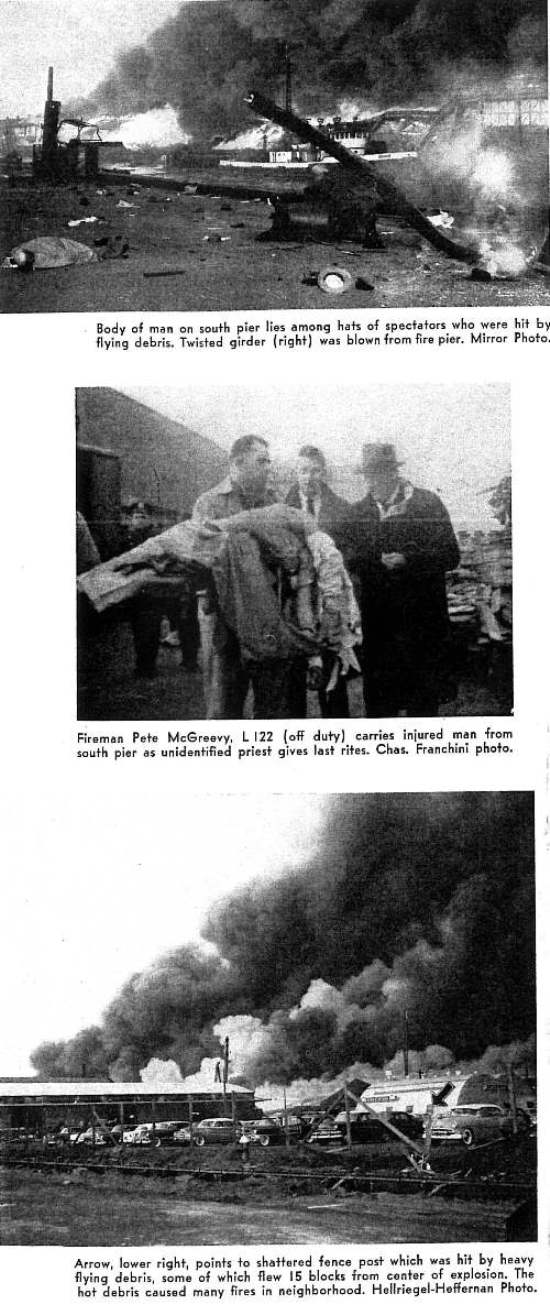

Captain John Purcell and Firemen McGreevy and Fernen of L 109 were opening skylights with 148. The explosion threw them to their knees as jagged objects rocketed overhead with bullet speed. Ten seconds later they were scrambling down the 35 ft. ladder 250 ft. shoreward without touching a rung. Someone yelled "Man overboard." They all ran to help pull Lt. Chall out of the water with an uncharged 21/2" line.

Acting Deputy Chief William Eisenhardt and his aide Jim McNamee ran for shelter as a 200 lb. chunk of hot pipe bounced alongside them before crashing into the 40th Batt. car parked on the corner of 35th and Marginal Streets. Batt. Chief John Murray never saw such havoc in all his 30 years of firefighting.

The first due unit, Eng. #228 had rolled onto the pier but were turned back by the heat and melting tar. Acting Lieutenant Al Kraemer sent the second alarm — one of the few times an acting officer had given such an order. This unit was operating on the north-side of the pier, opposite #278's position when IT happened. The blast rolled them all up a ball of arms and legs. Dom Proscia received a painful back injury. Out in front of the pier, MPO Frank Porcella started praying. He thought sure that his company had been wiped out. Joe Beetle thought his best bet would be to go overboard if it blew again.

Engine #201 was just behind the above company on the northside of the pier. Lieutenant Bill Alford yelled, "Hit the deck" and they all very promptly carried out the order. After the debris stopped falling, they wondered about the others.

Ladder #114 had just come down from the roof and were repositioning a ladder when the concussion blew the ladder into two pieces and threw the men to the ground. Firemen Werner and Lankewish were walking along with a 30-ft ladder. When it was all over, Werner was walking along with the remaining six rungs. This crew returned after the blast to assist the more seriously injured members.

Ladder #131 had been operating on the roof but returned to the front of the building where they were putting on their masks when they heard a sharp crack rather than a lound sound. They were protected by a cat-walk that joined the pier with the shed to the south.

Commissioner Edward F. Cavanagh, Jr., and his aide, Sid Klein, had just alighted from their car on 35th Street near Marginal Street when they were knocked over by the blast. They ducked under a parked car as a huge piece of pipe caromed off the 40th Battalion car, parked at the corner, and landed behind them. The Commissioner then ran toward the fire tortured by the thought of his men on the pier.

When Commissioner Cavanagh arrived at the pier entrance a fireman ran up to him and said, "Chief Conway is in there with a company, and they are probably all gone." Within an instant of this shocking observation, out of the smoke and debris walked Chief Conway and several firemen, all a bit shaken—hut, thank goodness, in good shape.

The Commissioner spent the next several minutes endeavoring to survey the extent of the casualties among the fire forces and setting a large force of volunteers to work to run down all possible sources of information as to what was stored on the pier, having in mind the horrible possibility of further explosions. Unfortunately, the Department forces had to continue controlling the holocaust without ever having any information as to what was on that pier. This in itself gives ample reason for giving thought to regulations requiring the posting of a cargo manifest in a safe area at the head of the pier and having someone on the pier at all times with a copy of the manifest in his possession.

Chief's Car Lifted

Chief of Department Edward Connors was responding to the fire on 35th Street and was half a block away when the blast actually lifted the car off the ground. Secondary fires started by falling debris were all over the neighborhood. The Chief used the radio to alert oncoming companies to these fires as well as to inform them of what positions to take on the pier. The Chief said, "In my 39 years in the Department I have seen miracles but nothing so miraculous as the fact that none of the firemen on the pier were killed."

Deputy Commissioner Harry Morr and his aide were getting fire clothes out of the trunk of his car when the blast came. The Commissioner grabbed a young boy who was passing by and pulled him into the shelter of the trunk until the debris stopped falling.

Engine 279 was midway up the stringpiece to the blast site when they were caught in the shower of debris. Lieut. Jake Dubinsky was hit in the hand and leg and Fireman Keough suffered shock and injury to both legs which caused him to be hospitalized. Individual thought was the same, "What should I do if this blows again?"

Engine 239 was in front of the main pier doors stretching a line from 282. Pat McCarthy, the MPO, ran behind the diner which suffered severe damage. When he saw the extent of the damage, McCarthy decided to set up the deckpipe because he thought he might be the only fireman alive and might have to hold the fort single-handed until help arrived. A body was lying at the spot where he had stood before the blast. The blast itself looked to him like "a black giant pouring acauldron of hot coals into a funnel." Lieutenant Ryan, who had his back to the blast when it occurred, was struck on the elbow by debris.

Assistant Chief Edward G. Conway had responded from Manhattan on the second and arrived just as the third alarm companies were going into position. Chief McGarry reported to him that he believed the best attack would be from the sides because of the intense heat and smoke within the pier shed. Chief Conway went in about 200 feet onto the pier to appraise the condition for himself. Terrific heat and smoke indicated that only very heavy lines could be effective. He was about to order them when the blast spun him around and knocked him down. Momentarily stunned and completely engulfed in black smoke, he lost his sense of direction. He headed for a lighter spot in the smoke which proved to be a cargo door — and safety.

Deputy Chief in Charge Edward McGarry, who arrived eight minutes after the second alarm, was directing companies opening cargo doors on the south side of the pier when it blew. He had been expecting a "smoke explosion" and cannot recall any loud noise but was made aware of the impact when 10-foot lengths of 4 by 4's and huge chunks of debris came raining down.

Frank Schmidt, Chief Conway's aide, was checking his pack-set radio in front of the pier building before following the Chief in when the blast came. As he ran for cover, Schmidt who had narrowly escaped death at the Bronx collapse last April had but one thought, "Keep that helmet on, Frankie boy." John Callaghan. Eng. 223, was left on housewatch duty when the Firefighter, berthed just one pier south of the fire scene, responded. He turned to see if the Gaynor (Eng. 51) was approaching when the blast knocked him sideways into the lockers. An instant before he had been looking at the fire through the very windows that shattered. Steam and water pipes burst and glass flew all over quarters. Callaghan ran out of the building which he thought would collapse — and then back again to get a towel to staunch the blood which was streaming down his face from a glass sliver driven into the bridge of his nose. The crew of a Police launch removed him from the pier. The clock, hurled from the wall, was stopped at 3:50 P.M. The only thing left working was the bells.

Chief Fire Marshal Martin Scott's car had reached Third Avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets when the explosion blew an iron girder about five feet long over a seven-story warehouse. It crashed in front of the speeding car and skidded underneath it. The Marshal thought that the engine had exploded.

Lieutenant Robert E. Lindgren of Ladder Co. 101, detailed to Eng. 202, was running back to his Company (that is, 202) with Donald Holton with orders to stretch in when the blast caught them 25 feet up from Marginal Street. Both were thrown to the ground. He lost his boots, helmet and wrist watch. He got up and continued running through the debris raining down to the pumper further up 35th Street. Since he couldn't fit under the new cars parked about, the pumper was his best bet. He found that several firemen and five civilians had the same idea. Art Leavitt, 202's MPO was looking toward the pier for a signal from Lt. Lindgren as the ball of fire rose high in the air and then seemed to boil over toward him. His first shocked conviction was that all the firemen on the pier roof had been killed. As debris began crashing down, he ducked under the pumper. Several days later when a WNYF representative interviewed him, Leavitt still found it hard-to believe that no firemen had been killed. "It's a miracle," he said.

After assisting Ladder 109 to raise a ladder to the pier roof, Engine 204 prepared to stretch to the pier from their pumper in front of the diner. The explosion sent them all scurrying for cover under parked cars, worrying whether the men on the pier roof were all killed.

Bob Riley of Engine 220 was driving that Company's pumper down 35th Street toward the pier when the concussion knocked him out of the seat to the ground. He jumped up and pulled the brake on the still rolling pumper and then dove under it with John Medici.

Holding the Fire

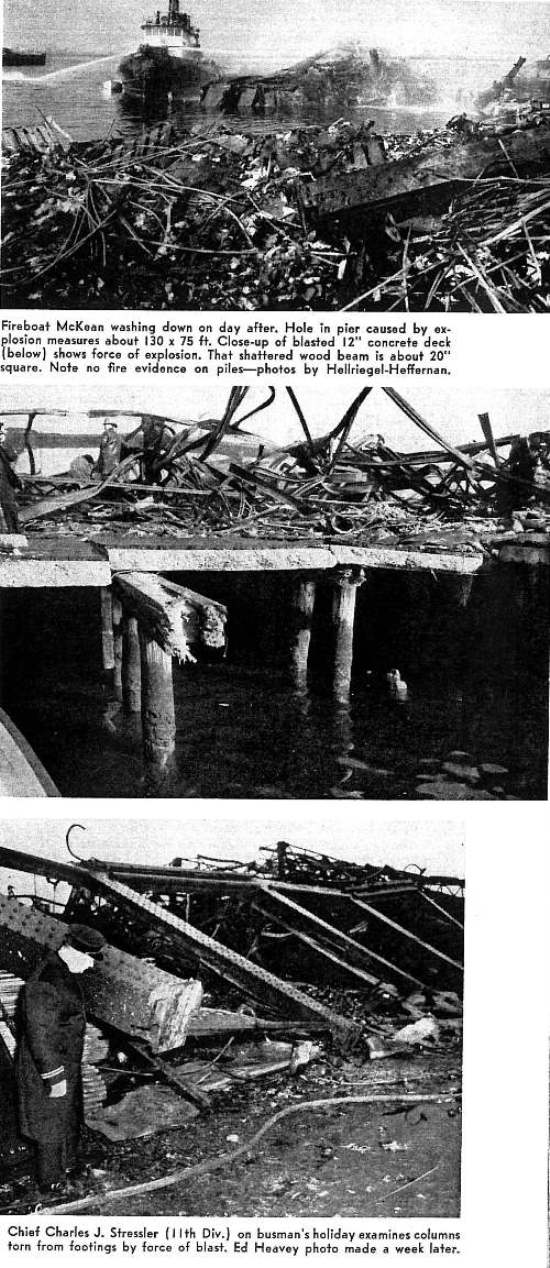

The miracle of holding such a huge body of fire was helped along by the courage and fast work of all concerned and the fine construction of the pier itself. When the blast occurred and huge chunks of debris tumbled out of the sky, the reaction of almost everyone on the scene was automatic. They ran or ducked for cover. But seconds later, everyone was on his feet — running back to the pier to save those who might still be alive. Hampered by dense smoke and terrific heat and certain that there was more explosive cargo on the heavily stocked pier, they nevertheless hurried along with the job of stretching and manning lines. Coast Guardmen and tugboat crews, police and clergymen were right in there needed, putting out adjacent fires, towing ships out of danger and ministering to the injured. Many heroic acts were performed in rescuing and caring for the victims of the blast. The work of Miss Pauline Tornello, R.N., a fire buff of long standing, was particularly outstanding. She had responded on the second and was in front of the pier when the explosion occurred. As the severely injured were carried off the pier, her white nurse's uniform served as the beacon to which the bearers converged. She applied First Aid and collaborated with the members of Rescue 2 in handling the wounded. Her cool efficiency and bearing under most trying conditions won the admiration of all.

Like Wartime Bombing

The waterfront area for blocks around the pier, after the blast reminded many of a wartime bombing. Glass and debris cluttered the streets. Most of the windows in all buildings within three blocks of the pier were shattered. More than 250 civilians were injured and ten killed. It seemed that the firemen nearest the fire were inside of the circle of destruction caused by flying debris. Heavy traffic in the area delayed the additional units—perhaps saving their lives. Both adjacent piers were shambles—doors on the pier to the north were blasted in and several small fires started. On the pier to the south where many spectators were injured, walls were blown in and roofs and skylights were lifted off. A pile of lumber blazed up and a-lighter caught fire and was set adrift. The freighter Greek Victory was tied up at the land end of the north side of the fire pier. Several small fires started aboard before she was cut loose and maneuvered to safety. Her whistle blew continuously adding to the general din of fire sirens and shouting spectators.

From the moment the third alarm was sounded for Box 1499, Dispatcher John Allen and his crew in the Brooklyn Central Office were flooded with emergency calls, requesting help for secondary fires started by the explosion, for ambulances, police reinforcements and special apparatus. The urgent messages were handled with a calmness born of experience and, in spite of the magnitude of the job. everything worked smoothly to the great credit of the Central Office crew.

Luck—or was it a miracle?—saved many from being killed by the falling debris. Looking at the area shortly after the blast, one could see that the universal statement, "It just missed me," was true. Here indeed was a "Miracle on 35th Street."

|