|

|

|

|

|

September 11, 2001

|

|

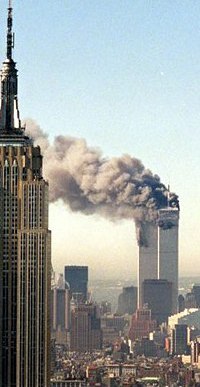

Covering Captain Ed Metcalf, working only his second day in Marine 1, listened to the change of the tour banter at the kitchen table. Marine Engineer Billy O’Brien, him of the infectious laugh and sunny disposition said,” There should be a law against working on such a beautiful day”. Everyone agreed. At 0845, the night crew of Marine 1 had mostly been relieved. The day crew was drinking coffee and discussing the day ahead as the first plane hit the WTC. The impact was heard but thought to be from a nearby construction site. Shortly thereafter, the voice alarm blared a second alarm for the World Trade Center. Captain Metcalf, aware of the proximity of the WTC to the Hudson River, shouted “Lets go”, and started the Fire Boat McKean on one of its longest, most arduous and certainly most important responses in its 45 year history. It was Tuesday, September 11, 2001.

|

|

|

While responding, the upper floors of the North Tower could be seen in the distance in flames, punching black smoke into the clear sky. As the McKean got closer, the men watched, in gut wrenching horror, as people began jumping from the upper floors, some in pairs, holding hands. Pilot Jim Campanelli brought the McKean into the sea wall at Liberty Street, just south of North Cove Marina. Captain Metcalf told the crew to assemble all the tools, spare masks, cylinders etc. on the fantail as Marine 1 would probably be a staging area.

|

|

He then told them to get ready to supply water and left for the command post for instructions. Injured civilians started arriving at the sea wall. Firefighter Billy Gillman spotted a man with severe cuts and burns to his head, wandering around aimlessly. Bill sat him on a nearby bench and rendered first aid. Afraid the man was in, or going into shock, Bill escorted him to a commuter ferry for transpiration to New Jersey. At 0910 a roar of jet engines was heard and everyone stopped what they were doing. A huge commercial airliner could be seen descending on the Manhattan skyline. FF Ed Weyrauch vocalized what was on each person’s mind. “What the hell is that guy doing” Moments later,in seeming slow motion, what he was doing became abundantly clear. As the plane crashed into the South Tower in a tremendous ball of flame, it was obvious to everyone that they had not responded to an accident, but an aerial attack. The number of injured arriving at the sea wall increased dramatically. Mostly they were civilians, but also Police Officers and Firefighters.

|

Others were assisting the most seriously injured. Each Firefighter arriving with injured, returned immediately to the scene to help others. During a lull, the crew decided to start stretching supply lines. Marine Engineer Dennis Thomson said no, as where the lines were needed had not yet been determined. FF Tom Sullivan said he would go see if he could find Captain Metcalf and receive orders.

|

After walking about two blocks east, Tom heard a thunderous noise and saw a cloud rushing at him, he turned and ran west. As he was enveloped in the cloud he was also knocked to the ground by the force of what he believed to be an explosion. Having lost his helmet, and crawling as fast as he could in complete darkness, Tom used his flashlight and found a curb. Small pieces were hitting him and he was sure larger pieces were to follow. He felt extremely vulnerable without his helmet. While crawling with his hand on the curb as a guide, Tom saw a small light about a foot off the ground. On investigating he was shocked to find that the light was at the end of a rifle. As it turned out, the rifle was in the hands of a NYPD Emergency Services Officer also looking for an escape. Tom told him he knew the way and together they found their way to the river and the McKean. The “explosion “ Tom heard was of course the collapse of the South Tower.

|

|

|

Captain Metcalf was at the command post just across from the WTC awaiting orders when the tower collapsed. He said he dove, not knowing which way or where and miraculously survived. He was pulled out of the debris and rushed to a hospital in Brooklyn and found to have only minor injuries and returned to the scene a few hours later. Other Officers and Firefighters standing only feet away were not as lucky. A full-blown panic was now underway at the sea wall. It was low tide and the steel deck of the McKean was 15 to 20 feet below the wall. Two ladders had been positioned to facilitate access and egress.

The scene was chaotic. Hordes of civilians, many incoherent, were trying to board the McKean. Several desperate people jumped the 15 to 20 feet to the deck, receiving moderate to severe injuries. One individual wanted to jump but was told to wait by Marine Engineer Bob Marshall. He jumped anyway and Bob tried to break his fall. Some of the civilians started untying the mooring lines to hasten their escape and had to be restrained.

|

|

Two women had jumped into the water to escape and were nearing the fireboat. A Jacobs ladder was put over the side and rind buoys were thrown to the women. The McKean is 130 feet in length and the freeboard is approximately 12 feet at amidships, preventing any hand to hand assistance to anyone in the water. The women obviously had been in the water for a while for they were exhausted to the point of being incapable of helping themselves. Observing this, Marine Wiper Greg Woods and Marine Engineer Gulmar Parga jumped into the water. The smaller of the two women was assisted onto the ladder and into helping hands on the deck. Greg and Gulmar succeeded in getting the larger woman to the Jacobs ladder and urged her to climb up. “I can’t do it, please just leave me” the emotionally distraught and physically drained woman replied. It was beginning to look like a failed effort.

|

To the amazement of all on board, Greg Woods dove under the water and physically raised this very heavy woman on his shoulders, assisted by Gulmar up onto the ladder enough to allow other men to partially climb down the ladder and precariously pull her to safety. By now fewer people were arriving at the wall. There were 200 to 250 people on board now including children and infants, handicapped people and oddly enough two dogs. Still not having heard from Captain Metcalf, the crew talked it over and decided it was imperative to somehow find medical help for the victims. Unsure of how this could be accomplished in the total chaos of Manhattan, it was agreed to go across the river to New Jersey.

Arriving in Jersey City in about 10 minutes, Pilot Jim Campanelli found he could not dock at the commuter ferry terminal due to shallow water at low tide. Going south to the next available dock, whose height was close to boat level, evacuation was started with enormous help from the civilians on board. However, a chain link fence and wooden barricade, on the other side of which emergency services from Jersey City were arriving, blocked access.

Tom Sullivan took a partner saw from the boat and cut the chain link fence and wooden barricade and allowed access to the emergency services Jersey City provided.

|

While getting the victims off the boat and receiving that familiar feeling that you are getting the upper hand and can almost see light at the end of the tunnel, someone screamed “NOOOO”, while looking toward Manhattan. Everyone stopped what they were doing and watched horrified as the second tower collapsed. As soon as possible, the McKean had returned to Manhattan. A few civilians asked if they could return with us to help. They were welcome and in retrospect its obvious we could not have functioned the way we did without the assistance of numerous, unnamed civilians throughout the disaster. Everyone at this point was to some degree, in shock. That all tasks continued to be performed under these conditions is nothing short of astounding. Heading back to Manhattan from Jersey, not knowing what was happening or for that matter what happened, other than what you personally observed, was bewildering. A few members confided that they thought they were returning to New York to die. Approaching the sea wall again there was a group of Firefighters waving the McKean in at the foot of Albany Street.

|

|

|

Pilot Campanelli brought the boat in there and tied up. The firefighters said there was no water in the hydrants and they needed water immediately.

Firefighters, Engineers, wipers, and civilians started stretching supply line from the McKean toward the WTC site. Off duty members of Marine 1 and other units were arriving to help at this time. Some members asked for and received masks, bunker gear, helmets, flashlights, etc., much of which was not recovered.

|

|

Visibility was still very poor due to the amount of dust in the air. 3 ½ inch supply lines had to be manhandled all the way to West Street in the choking irritating atmosphere. It was late morning now and Marine 1 off duty members, fortunately, were arriving in ones and twos. A steady stream of civilians were still arriving and were assisted on board and then transferred to police and Coast Guard launches pulling up on our port side where they were evacuated to points unknown. Due to the length of supply lines, it became obvious that we would be out of 3 ½ inch hose soon. The fireboat Kane and tender Smoke after responding into North Cove and evacuating civilians responded back to the quarters of Marine 1 at Bloomfield Street and retrieved spare fittings and numerous lengths of old hose, which fortunately had not yet been transferred to technical services.

|

This old hose, some of it from the 1960's did create somewhat of a problem, though it was a godsend. The Fire Department had switched all couplings on 3 ½ inch hose to 3 inch. Much of the old hose still had the outdated 3 ½ inch couplings. Fortunately, the engineers and wipers found enough adapters and resolved the problem. Subsequently, pallets of new 3 ½ inch hose was delivered to the Albany Street site.

By early afternoon, all members of Marine 1 were present, alternately searching the collapse for victims, manning the previously decommissioned fireboat Harvey, stretching lines and manning the tender Smoke.

Communications or lack thereof, was an ongoing problem. Engine company chauffeurs manning the pumps at on scene engine companies were from other companies on and off duty and pressed into service, didn’t know where the assigned Engine Company Chauffeurs were, did not know where their water supply was coming from nor where the lines they were supplying were going to. To further exacerbate the problem, they were not equipped with hand-talkies.

The first supply line was to a manifold opposite 90 West Street. The second and third lines were supplying E-219 at the intersection of Albany and West Street, adjacent to 90 West Street. At one point 90 West was thought to be in danger of collapse due to numerous interior fires. The area was evacuated on orders received via handi-talkie, leaving both the manifolds and E-219 pumps unmanned. After about ½ hour, firefighters unfamiliar with inactivity at a disaster started filtering back to continue doing what they could. (90 West Street still stands)

|

Though the McKean was pumping at capacity, water pressure at West Street was barely adequate due to the long distance. D.C. Mosier, sector chief at Albany and West Streets, had E-228 and E-216 respond to Albany and South End Avenue. With the assistance of firefighters on scene, many from New Jersey communities. These pumpers were inserted into the supply lines, each receiving two 3 ½ inch lines and relayed water to West Street. This was done to build the volume of water coming from Marine 1 to pressurize water, so firefighters in these buildings could fight the many fires. Subsequently E-14 at the same location and was supplied with a 3 ½ inch for relay.

|

|

|

Two of the 3 ½ inch supply lines to E-219 could not be interrupted due to the fact that it could not be determined who or what they were supplying and how critical those lines were. Later in the afternoon, members of Marine 1 took over the manning of two of the Engine Company’s pumping water to the site. By that night, fuel in these Pumpers became a problem. The Engineers from Marine 1 with 5 gallon cans of diesel and funnels from the McKean put fuel in these pumpers to keep them going until the Fire Department could get their Fuel Truck to the scene.

At about 2100 hours an engine company from the West Orange New Jersey F.D. arrived at the foot of Albany Street and said they had 5 inch hose that could be used to relay water if needed. After Marine Engineer Dennis Thomson, who had been the de facto OIC most of the day, determined that the fittings were compatible, the West Orange pumper was escorted to Albany Street and South End Avenue, where the three FDNY engine companies were already relaying water east. However, the West Orange unit did not have enough hose to go all the way to West Street. Still, more water could be supplied to the scene by supplying them with 5 inch hose and relaying with 3 ½ inch hose. At this point the Patterson Fire Department arrived and it was determined that not only did they have 5 inch hose, but the couplings were compatible with those of West Orange.

After lines were stretched and connections made, D.C. Mosier was informed that in effect, a 5 inch water main was now at his disposal at West and Albany Streets. Soon after construction equipment was arriving to start moving the many cars, trucks, and debre from around the scene. With the hose lines stretched across some of these streets, this became the next problem. Marine 1 Lieutenant Harry Wanamaker reported this to the D.C. Mosier, and was told to do what ever he had to, to solve the problem. Lt. Wanamaker had one of the construction crews trench the street, then had the hose lines moved into the trench and covered with wood so the trucks could pass without cutting the water supply.

|

|

At about 2300 hours a message was received in a round about way, that the Fire Department would go to a two platoon, 24 hour on 24 off schedule commencing at midnight, with the tours changing at 0900 daily. What that meant was that half of the members would be relieved at midnight and return at 9 AM for 24 hours. The other half would remain on duty until 0900 hours on Wednesday. In effect, some members would remain on duty for 48 continuous hours. Due to communication problems, some members remained on duty longer than that.

|

Exhausted, dirty angry and frustrated, some members refused to leave. Some were ordered to go back to Marine 1to get some sleep. Every FDNY engine company carries several lengths of 3 ½ inch hose for relay or to supply stand pipes. Marine 1 stripped every available engine company of all 3 ½ hose, utilized all 3 ½ hose on the boat, all old hose retrieved from quarters and all new hose delivered by technical services. It is estimated that Marine 1 supplied approximately 250 lengths of 3 ½ hose and 20 lengths of 5 inch hose during this operation, without exceeding its capability.

Marine 1 continued supplying water as the DWS gradually repaired, or isolated, the damaged water mains until sometime Friday, September 14th. Marine 1 stayed at the scene about 2 weeks, while sending crews to the scene to help dig on the pile.

This recountment of those days was written by Captain Tom Tracy with extra details added by Bob Petersen.

|

| |

|

|

|

|